IN THE WINTRY THICKET OF METROPOLITAN CIVILIZATION

Yin-Ju Chen & James T. Hong, Basim Magdy, Mores McWreath, Pietro Mele, Camilo Yáñez

Curated by Luigi Fassi

In the Wintry Thicket of Metropolitan Civilization refers to an eponymous passage from The Culture of Cities, the first book by Lewis Mumford, published in 1938. His fervid analyses connected the militant power and intellectual lucidity of the attempt to rethink urban development with a profound humanist approach. Thus, the Culture of Cities was the formulation of numerous urban projects and hopes, which were defined within the concrete aspect of a planning praxis that aimed to place attention on the role of cities as decisive centres of contemporary living, in the civilisation of the 20th century and the near future. The exhibition gathers together the artistic experiences of five artists deriving from different continents who reflect in their work on various topics related to urbanism and the history of urban development. Between the recent past and an imagined future, the works freely echo the enigmatic sense of the title, which according to Mumford was meant as an alarm signal, but at the same time also an urgent need to rethink the concept of human living space, starting with the most important and decisive place of aggregation and collective occupation: namely, the city.

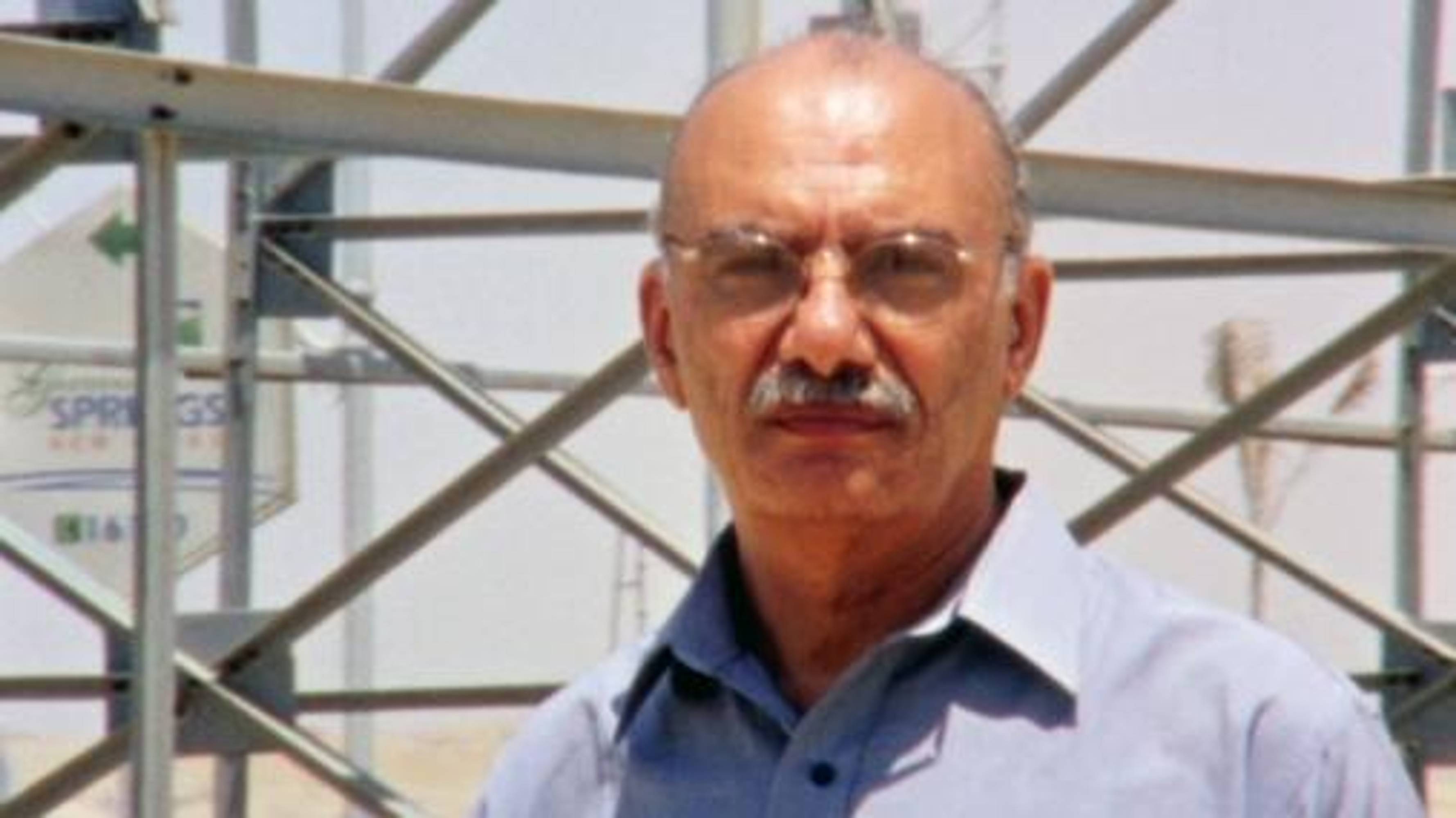

My Father Looks for an Honest City (2010) is a film by Basim Magdy which shows the desolate location of the periphery of Cairo in expansion, marked by anonymous buildings under construction, water-logged streets and stray dogs. As a place of transition between cement and wild plant growth – not yet totally urbanized but at the same time no longer rural – the site is slowly traversed by the artist’s father, who holds in his hands a shining lamp in broad daylight, exploring the territory without any clear aim. Within this work, the reference to Diogenes the Cynic, who provocatively “searched for an honest man” by holding up a lamp in daylight while strolling through the markets of Athens, is clear. Through his paradoxical gesture, Diogenes brought about a radical critique on his fellow citizens’ lack of a more responsible role regarding their social reality. The philosophical re-enactment staged by Magdy evokes the same suggestion in intuitive terms, conferring to his father’s minimal gesture the capacity of reading an anonymous territory in analytical terms. He thus poses questions on the destiny of Cairo and contemporary Egypt. You Have Never Been There (2010) by Mores McWreath is a 90 minute-long film that freely assembles scenes from 120 different films that have addressed the end of human civilization in apocalyptic terms. The artist has selected scenes in which passages showing devastated urban and natural spaces evidently alternate, marked by the remains of Western civilization and a present reality of decline and dissolution In this way You Have Never Been There is a portrayal of Western civilization after its demise. It is an allegorical description of progressive self-destruction, in which the aesthetics of cinematography as a means of fictional narrative is removed by the artist in order that the scenes become an actual documentary, as evidence presented in advance of a probable future scenario. End Transmission (2010) by Yin-Ju Chen & James T. Hong is a film of black and white images of metropolitan areas succeeding each other compose an indecipherable landscape, characterized by a sense of surveillance and enslavement. The messages that appear discontinuously throughout dictate the new program of administration of their planet by an indefinite alien entity. From the imperative contents of the texts it is deducible that humanity has failed and that a radical intervention of palingenesis by an extraterrestrial power has been necessary. This science fiction suggestion is supported within the rigorous cinematography of the two artists by authentic images of industrial platforms, endless views of megacities by night, artificial greenhouses and mass consumption ready for export. Shot between Europe and Asia, the scenes of Yin-Ju Chen and James T. Hong allude to the current transformations of the great contemporary metropolitan contexts and industrial production on a large scale. In this way they allow a dramatic image of the alienation of our life and of contemporary work on a global scale to emerge. Beginning with research in the micro-reality of present-day Sardinia, the Italian artist Pietro Mele presents a critical reflection on the trauma of modernity which was imposed on the pastoral life of the island. Ottana (2008) is the title of his film and also of an eponymous small town in the area of Barbagia, where from the 1960s onwards a giant petrochemical industry with devastating environmental impact has been created. The work speaks of the blatant compromise between the world of heavy industrial production and the everyday life of the workers that maintain – as far as the factory gates – their traditions and residual customs that seem to belong to an almost extinct world. Urbanization and industrial work appear within Mele’s work as a nightmare deriving from somewhere else, a monstrous visual hallucination that places against the rural background the image of the Sardinian workers trudging in a row towards the factory. The focus of Estádio Nacional (2009) by Camilo Yáñez is the city of Santiago de Chile and the dramatic events it was witnessed in recent decades. The film was shot by the artist on 11 September 2009 in the National Stadium of Santiago, a key place in the contemporary history of Chile. The stadium entered the collective memory of the nation after the coup d’état of 11th September 1973, when General Pinochet liquidated with the support of the US government the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. In the turmoil of the days following the military‘s seizure of power, the stadium became a prison camp where over 3,000 people were killed by the forces of the newly-established military dictatorship, as official sources document. Yáñez shot the film inside the empty stadium, accompanied by a famous song from the national Chilean repertoire. Thus, Estádio Nacional is a tribute to the history of Chile and at the same time a funeral elegy commemorating the victims of the coup d’état of 1973, but also an invocation of hope in a place that has alternatively witnessed the most dramatic hopes and the most sinister events in the history of the Chilean people.