UN MITO ANTROPOLOGICO TELEVISIVO

Alessandro Gagliardo

Curated by Luigi Fassi

The work of Alessandro Gagliardo focuses on the impact that the documentary nature of television news exercises on the construction of a mytho-poetic interpretation of contemporary Sicilian history. The project entitled An Anthropological Television Myth (Un mito antropologico televisivo) deals with the decisive years between 1991 and 1994, during which a number of different events changed the course of Sicilian and Italian history. From the Mafia killings endemic to the region, culminating in the murders of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino in Palermo, to a spiralling housing crisis in which abusive building practices went unchecked for decades, the first half of the Nineties can be characterised by a growing conflict between state and citizens, and by a general political reorganisation the ramifications of which reverberate to the present day.

Gagliardo’s artistic research is here divided into several chapters, in order to build a complex narrative of these events based on everyday life in the province of Catania and its villages. Gagliardo uses archival materials to document the journalistic record made by local television programs at the time.

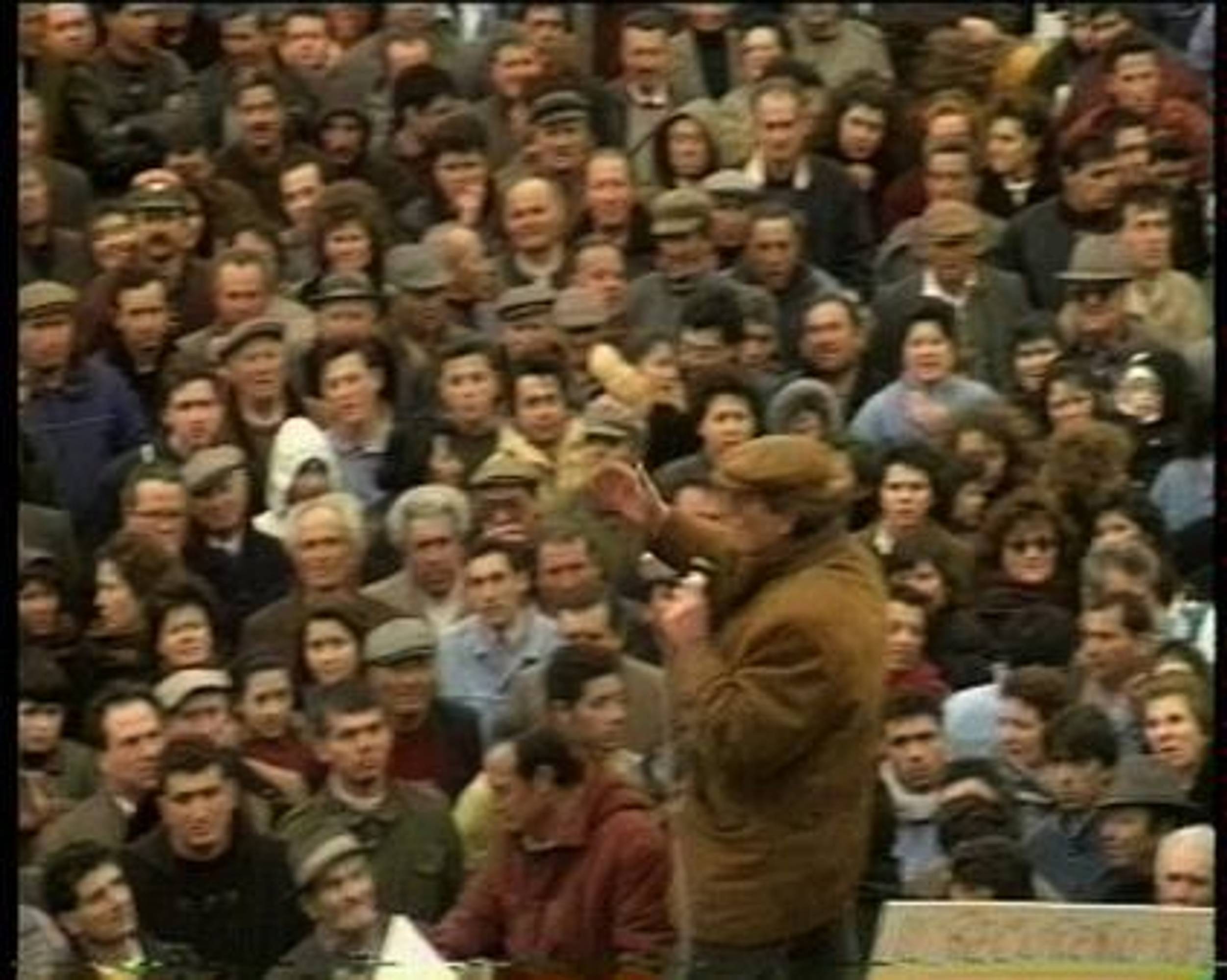

Mitografia (Mythography, 2011) is a video project comprising more than a hundred and twenty thousand photographs of masses of people, capturing their facial features, expressions, and states of mind. Mythography consists of slow-motion sequences of television footage filmed during public protest demonstrations in the Catania region during the early Nineties. It is intended to lead to contemplation on the anthropological transfiguration of society as revealed through television documentaries.

The cultural sensibility Gagliardo displays in Mythography is echoed in Città Stato (City State, 2011). This work is closely related to an intellectual tradition which since the 1940s has sought to reveal the crisis of the Italian Mezzogiorno, and, at the same time has pointed out the social and political potential of this territory to resist the decline resulting from the practices of Italian neo-capitalism. Gagliardo’s work seems to revive certain traditions—ranging from Carlo Levi’s forays into Southern Italy and his subsequent books documenting these jouneys, the political and literary actions of Antonio Gramsci, Rocco Scotellaro and Danilo Dolci, to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s denunciations of the genocide inflicted on the cultural world of rural Italy—by focusing on the interpretation of the anthropological nature of Sicilian society in the early Nineties. Gagliardo explores the increase in the number of Mafia killings during this period through an in-depth survey of the world around Catania, one in which homicide and brutality were accompanied by a sense of civil unrest generated by an epidemic of unauthorised building activity and the impossibility of finding any source of mediation between citizens and authorities. His work is not composed of refined, elegantly edited reportage, but rather of a chaotic mass of raw archival footage representing hours of film material accumulated by the local television stations in their discovery of the real Catania—before being “cleaned up” and “packaged” for eventual broadcast.

The same logic is at work in Dei poteri e delle povertà (On Powers and Poverties, 2011), an installation comprising hundreds of printed freeze-frame photographs selected from the same original masters of S-VHS material made by local Catanian television at the time. As the title suggests, this work is a dramatic visual composition spotlighting juxtaposition, abuse, and misery, documenting the ebb and flow of everyday life on the streets of cities like Biancavilla, Adrano, Misterbianco, Santa Maria di Licodia and Paternò. The settings range from places where Mafia killings have occurred to tombstones and urban cityscapes, from rural landscapes to the peripheries of cities. The presence of microphones in the foreground is a decisive element of the iconographic metamorphosis of these scenes: this emphasises the mediation that has occurred between the television cameras and reality, between everyday experience and journalistic narration.

This process of anthropological sublimation reaches its peak in Filosofia della miseria (Philosophy of Poverty), the video presentation of archival footage of a small village graveyard in the province of Catania. In the desolation of a walk through the graveyard—amidst anonymous heaps of earth surmounted by crosses, burial niches and grey-haired visitors—these television images exude a sense of devastation and penury. Here again, the simple visual record made by a cameraman and revisited by Gagliardo, becomes a source of universal material of documentation, representing miserable fragments of time in a poverty where even death seems stripped of itself—and is thus transformed into a deconsecrated myth that awaits its possible redemption at some point in the future.